USDA Vet Shortage Areas: What It Means for Your Farm

By Thomas Blanc, Founder · Published January 2026 · Updated February 2026 · Based on verified data from our directory of 9,500+ practices

What Is a USDA Veterinarian Shortage Situation?

The USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) maintains an official list of geographic areas designated as Veterinarian Shortage Situations (VSS). These are counties or multi-county regions where access to large animal or food animal veterinary services is inadequate relative to the number of livestock and the health needs of those animals.

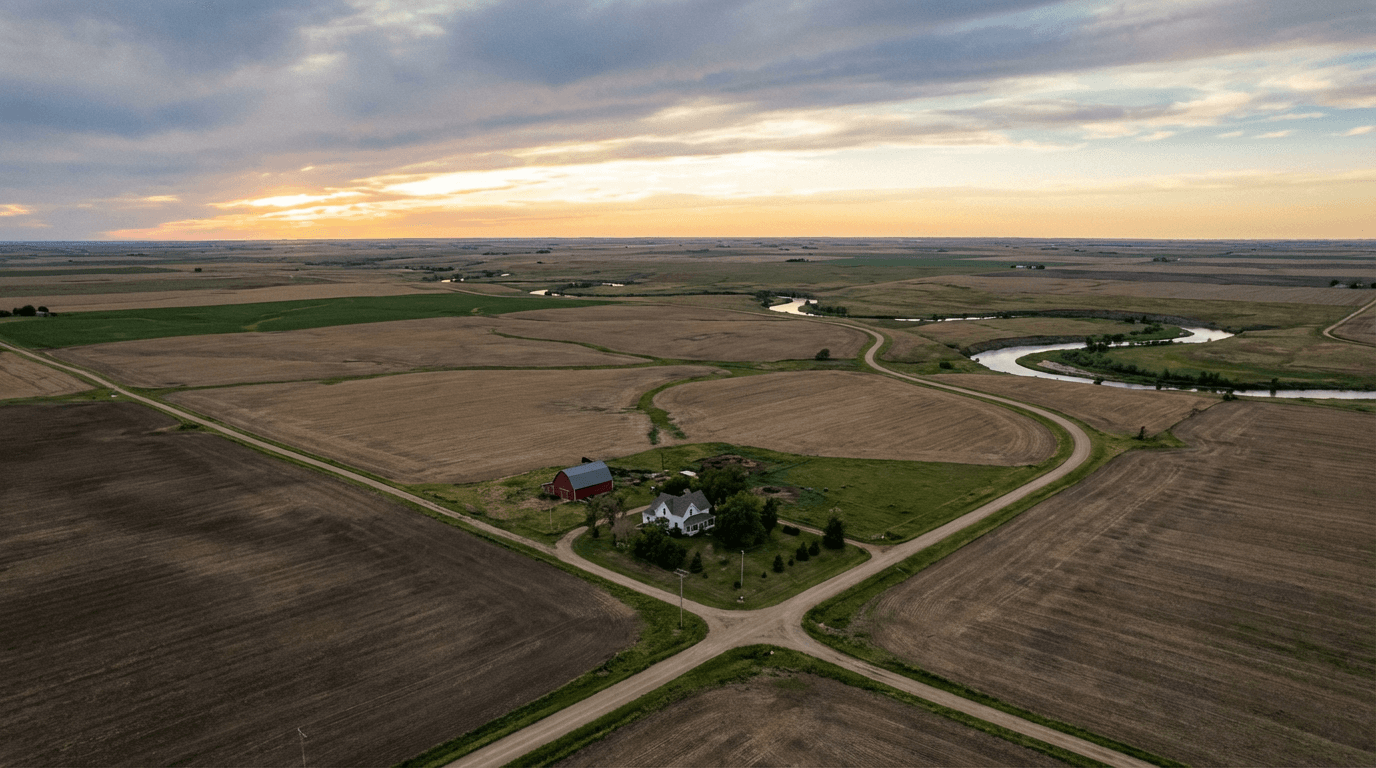

As of 2025, more than 200 counties across the United States hold VSS designations. The problem is especially acute in the Great Plains (Montana, Wyoming, the Dakotas, Nebraska, Kansas), the Mountain West, and many rural counties across the South and Appalachian region.

A VSS designation is not just a bureaucratic label. It is used to prioritize resources, direct loan repayment programs for veterinarians who agree to practice in those areas, and allocate government support for rural veterinary infrastructure.

Why the Shortage Exists

The rural large animal vet shortage is a structural problem with multiple causes that have been building for decades:

- Economics of large animal practice. Large animal calls require significant travel time, physical labor, after-hours availability, and expensive equipment. Revenue per hour is often lower than in small animal practice. New veterinary graduates carrying $200,000 to $300,000 in student debt are making economically rational — if devastating for agriculture — decisions when they choose urban small animal or specialty practice over rural mixed practice.

- Veterinary school debt load. Average veterinary student debt is now well above $150,000. In rural areas, a large animal vet may earn $80,000 to $110,000 annually — enough to live on, not enough to service debt rapidly and build a practice.

- Aging workforce. The average age of rural large animal practitioners is rising. Many established vets have no succession plan and will leave behind uncovered counties when they retire.

- Consolidation of agriculture. Larger, fewer farms mean some areas have fewer farm clients to sustain a vet practice. The commercial operations that remain often contract directly with large veterinary firms rather than relying on local practitioners.

- Quality of rural life factors. Isolation, long hours, physical demands, and distance from urban amenities deter many graduates from choosing rural practice.

Which States Are Most Affected

While VSS designations exist in nearly every state, the concentration is highest in:

- Montana, Wyoming, Idaho — vast land area with sparse vet coverage. Single vets may cover 5,000 square miles.

- North and South Dakota — extensive ranching country with shrinking vet populations.

- Nebraska, Kansas — large cattle state with pockets of very poor coverage in the Sand Hills and other remote areas.

- Appalachian region — eastern Kentucky, West Virginia, southwest Virginia — significant small-farm livestock activity with minimal large animal vet access.

- Mississippi Delta and rural Alabama/Georgia — poultry and cattle country with vet access gaps in some counties.

USDA Programs to Address the Shortage

Veterinary Medicine Loan Repayment Program (VMLRP)

The VMLRP is the federal government's primary tool for incentivizing vets to practice in shortage areas. Eligible veterinarians who agree to practice for at least three years in a designated VSS receive loan repayment assistance — up to $25,000 per year (plus a federal income tax "gross-up" of about 39% to offset tax liability on the payment).

For farmers: this program is why your county's VSS designation matters. A county with a VSS designation can attract loan-repayment vets who might not otherwise choose that area. If your county does not have a VSS designation and you believe it should, contact your state veterinarian or your county Extension office.

Veterinary Services Grant Program (VSGP)

USDA NIFA funds grants to accredited colleges of veterinary medicine and other entities to establish, expand, or maintain veterinary services in shortage areas. These grants have funded rural veterinary internships, mobile clinic programs, and telemedicine consultation infrastructure.

National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) Training Grants

NIFA funds specialized training in rural large animal practice, including training in areas like food safety, USDA accreditation, and rural emergency response, to make rural practice more attractive and financially viable for new graduates.

What Farmers Can Do in Shortage Areas

If you farm in a vet shortage area, the situation is real, but you are not without options:

Establish a Relationship with the Nearest Available Vet

Even if the nearest large animal vet is 80 miles away, establishing yourself as an active client — paying promptly, having animals ready, scheduling efficiently — gives you priority access when emergencies happen. A vet will drive 80 miles for a good client they have a relationship with. They may not for a stranger calling at midnight.

Use Veterinary Telehealth for Non-Emergency Consultations

Telehealth platforms like VetNOW, TeleVet, and others allow you to consult with a licensed veterinarian via video. For triage decisions, medication questions, and follow-up on ongoing conditions, telemedicine is a legitimate and increasingly insurance-covered option. It does not replace a farm call for physical examination or procedures, but it reduces unnecessary calls and helps you manage between visits.

Build Your Own Skills

In shortage areas, farmers who learn to perform routine procedures — administering injections, passing a stomach tube, basic wound care, dystocia assistance — are better positioned to manage between vet calls. Many land-grant Extension offices offer livestock first-aid and basic husbandry training. Ask your vet to train you in the procedures they are comfortable having you perform under their supervision.

Form a Producer Cooperative

In some shortage counties, producer groups have successfully contracted directly with a vet for scheduled regular visits, essentially guaranteeing the vet a minimum income for a monthly or quarterly circuit. This model works when enough farms coordinate. Contact your state livestock association for examples.

Contact Your State Veterinarian

Every state has a State Veterinarian (a USDA APHIS-affiliated position). If your county lacks adequate large animal vet access, your State Veterinarian's office can provide information on VSS designation petitions, emergency coverage, and state-level programs. Find your state contact through USDA APHIS.